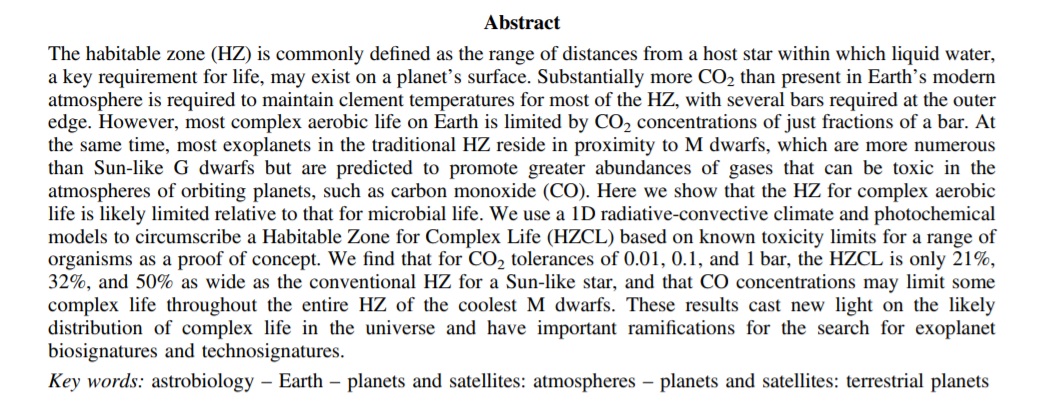

One of the most important skills any discerning media consumer can have is the ability to comprehend a scientific research paper. Reading a paper won’t imbue you with the ability to understand all the science behind it, but it could help you debunk BS when you see it on the news or social media. There are numerous types of research papers, but we’ll just focus on primary research papers – the kind you’re most likely to encounter worth reading. The first thing you should do once you’ve found a paper you want to read is figure out who wrote it and what organizations they represent. We’ll use the following paper from the Astrophysical Journal as an example, if you’d like to follow along. The authors’ information is usually located at the top of the paper, but sometimes you’ll have to scroll to the bottom of the paper to find the “authors” section. The first name listed is normally the “lead” researcher on the paper. The numbers beside each name correspond with the list of organizations underneath. Here we see the work was conducted by scientists from several universities, labs, and NASA. If it’s not immediately apparent where the researchers work/study, consider Googling the names to see if they are legitimate scientists. Now that we’ve figured out who wrote the paper, and we’re confident it was published in a reputable journal, we’re ready to dive in. First off there’s the “abstract” section. This is the researchers’ summary and there’s different schools of thought on whether you should read it first. If you’re confident in the research – as we are here, based on who conducted it and where it was published – you can go ahead and read the abstract. It’ll give you a good idea of what the paper is about and how the research went. If you’re not so sure, you should probably skip it because the abstract is the researcher’s direct interpretation of their own work, not the scientific community’s peer-reviewed summary – it could be biased. Next you come to the introduction. This is where you’ll find out what question(s) the researchers are trying to answer. Pay careful attention to word usage here and don’t get too hung up on mathematical or scientific concepts you’re not trained to understand. It’s useful to be an expert in calculus when reading an AI paper, for example, but it’s not necessary to comprehend the general information within it. What follows the introduction are usually a few sections on methodology and procedures. This is where you’ll find the meat of the research, how studies were conducted, and what steps the scientists took. This part is often the densest of the paper, and it’s usually the most important. It’s here you’ll find out how the researchers came to their conclusions. Next you’ll find the discussion portion. Things tend to get interesting here, the researchers usually talk about the implications of their work, what they discovered along the way, and how it related to previous work. Finally, you’ll arrive at the conclusion. This shouldn’t tell you anything you don’t already know if you’ve read the introduction and main body of the paper. But it often contains more information about the results of the research than the abstract does, and sometimes the scientists will disclose what’s next for the work.Reading and understanding research papers isn’t something you can learn to do overnight, it takes practice. And you can’t just skim them to get the gist either. You should expect to spend anywhere from an hour reading short papers to five or six for longer ones. But it’s an important habit to get into. When it comes to science claims: doing your own research means more than watching YouTube videos or reading the news.